by Nedra Weinreich | Apr 11, 2007 | Behavior Change, Blog, Social Marketing

As I was catching up with my pile of unread Wall Street Journals, I came across a couple of articles that at first glance had nothing in common.

As I was catching up with my pile of unread Wall Street Journals, I came across a couple of articles that at first glance had nothing in common.

The first (Crop Prices Soar, Pushing Up Cost of Food Globally) talks about how the recent turn toward producing environmentally friendly biofuels has driven up the price of food worldwide and may force central banks to raise interest rates in order to fight the resulting inflation.

One of the chief causes of food-price inflation is new demand for ethanol and biodiesel, which can be made from corn, palm oil, sugar and other crops. That demand has driven up the price of those commodities, leading to higher costs for producers of everything from beef to eggs to soft drinks. In some cases, producers are passing the costs along to consumers. Several years of global economic growth – led by China and India – is also raising food consumption, further fanning the inflationary pressures.

So environmentalists who think they are only doing good by using their Willie Nelson biodiesel may in fact be increasing the numbers of starving people in developing countries – certainly not what they intended.

The other article (The Backlash to Botox – which I was not able to find reprinted in full anywhere) recounts the difficulty that television casting directors are having in finding actresses who do not have Botox-frozen or surgery-enhanced faces. They just can’t find women who look their age, or who are able to create appropriate facial expressions. With high definition television, these cosmetic procedures become even more apparent (“The Botox used to be less noticeable but high def has changed that,” says one network president. “Now half the time the injectibles are so distracting we don’t even notice the acting.”) Ironically, many of these women started using Botox specifically to look better for the camera and to hide their wrinkles from the close-ups.

The common thread between the two articles, as you have probably already figured out, is that you cannot always predict all potential consequences of a particular behavior. Inevitably, someone somewhere will do exactly what you want them to do, which will somehow set off a sequence of events that leads to a bad outcome of some sort. Whether it’s your campaign to get women to call for an appointment for a mammogram that overloads the local hospital’s phone circuits and prevents other patients from being able to get through, or an exercise program that leads to overzealous participants with twisted ankles and shin splints, you may not be able to predict all possible outcomes.

So how do you deal with the unforeseen when you don’t know what exactly you are looking for? First of all, continue to stay tuned in to your target audience (you know who they are, right?). Pay attention to what they are talking about. Listen to personal anecdotes. And continue to look downstream from the point where you are engaging them in behavior change. What are the positive things that are happening? What else are people doing related to that change? How are others outside of the target audience responding to your campaign or to the people who have adopted the behavior change? Have social norms shifted one way or the other? Have power dynamics changed, and with what effect?

While chaos theory may not be entirely appropriate to use to describe the effects of human behavior, it’s certainly true that small changes can trigger other unforeseen events down the line. One person’s footsteps can set off a massive avalanche. Being aware of that possibility, rather than assuming that effects of the intervention will be confined to the variables in our logic model, is the key.

Photo Credit: ariel.chico

by Nedra Weinreich | Jan 31, 2007 | Behavior Change, Blog

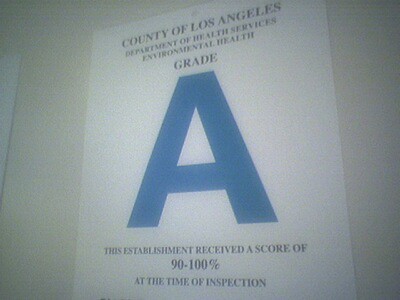

One of the things I love about Los Angeles County is that every restaurant (and other establishments that serve food) is required to post the results of its most recent health inspection in the window by the entrance. Depending on the score they received for about 100 different factors like food temperatures, food preparation practices, vermin (yuck!) and presence of hot water, the restaurants are assigned a grade of A, B, C, or the actual score if below 70. The signs (which look like the picture above) have to be posted, and they are large enough that they can even be seen by someone driving by.

Perhaps this doesn’t seem like a big deal, but this was a brilliant idea on the part of the LA Public Health Department. This system has been in place for perhaps about 10 years, and LA was, as far as I know, the first to adopt this idea. Though it’s old news around here, it’s still a groundbreaking system for a couple of reasons.

First, it puts power into the hands of restaurant customers, who can make an informed decision whether they want to risk getting a foodborne illness from a restaurant that is not following entirely safe food preparation and storage practices. If I don’t see an “A” in the window, I drive right by and go somewhere else. Why take the risk? Before this system, the only way we’d know that the restaurant did not pass its health inspection with flying colors is by asking the restaurant or the health department. I doubt that happened very often.

Second, it puts pressure on the restaurants to make sure they get an “A.” While they will probably not be closed if they receive a “B” (unless there are code violations that necessitate shutting down until the problem is fixed), the negative effects of the lower grade means they will have fewer customers, who may not return even when the grade returns to an “A.” In my experience, word of mouth spreads quickly when a popular restaurant loses its top grade, and even people who do not see the grade in the window themselves stay away.

Imagine if this system spread to other industries: cell phone companies required to post the number of complaints they received that month right on their websites, airlines required to post their scores for flight delays and lost luggage, hospitals with a placard out front showing how many of their patients came down with a hospital-acquired infection last month… We would come closer to Adam Smith’s vision of using perfect information to let the invisible hand work its magic in the marketplace. And we could all make choices that would leave us healthier and happier.

Photo Credit: hawaii

Technorati Tags: health, ratings, los angeles, restaurants, food

by Nedra Weinreich | Jan 8, 2007 | Behavior Change, Blog

And we go from talking about celebrity spokespeople to looking at peer role models. Real people who have made positive changes in their lives can be great motivators of change in others. Of course, this is classic Bandura. His Social Learning Theory says that when we observe someone else engaging in a behavior and receiving positive consequences as a result, especially if the role model is similar to ourselves, we are much more likely to try out that behavior as well.

And we go from talking about celebrity spokespeople to looking at peer role models. Real people who have made positive changes in their lives can be great motivators of change in others. Of course, this is classic Bandura. His Social Learning Theory says that when we observe someone else engaging in a behavior and receiving positive consequences as a result, especially if the role model is similar to ourselves, we are much more likely to try out that behavior as well.

This is why GlaxoSmithKline only sought out actors for its commercials for NicoDerm patches who were smokers or former smokers. And why its new campaign for Commit nicotine lozenges will follow four real people over 13 weeks as they attempt to quit smoking. Watching someone else struggling with quitting and succeeding provides much more useful information in someone’s own attempts than inauthentic actors reading lines.

And this is why one woman was able to inspire her community to lose 8,000 pounds. I recently received a prepublication copy of a book called From Fat to Fit – Turn Yourself into a Weapon of Mass Reduction. The author, Carole Carson, relates the story of how her own efforts to lose weight (62 lbs.), which were chronicled in her local newspaper, turned into a community-wide fitness campaign called the Nevada County Meltdown. This effort — run entirely on a free, volunteer and ad-hoc basis — involved over 1,000 participants, who lost nearly four tons of weight in eight weeks.

Now, with Carole’s book coming out in April, she is offering her guidance to another community to replicate the success they experienced in Nevada County (Calif.). She is sponsoring a contest to select the next Community Meltdown location. If you are a professional working on obesity prevention, or if you are a motivated individual who wants to help members of your community become healthier, think about entering the contest — all it takes is a 2-minute VHS or DVD spot on why your community should win, along with a 150-word written plan. You don’t get any funding for it, but you do get the benefit of Carole’s experience and lessons learned. And hurry, because the deadline is January 30, 2007.

Technorati Tags: obesity, weight loss, fitness, health

by Nedra Weinreich | Dec 13, 2006 | Behavior Change, Blog, Social Marketing

Monday’s Wall Street Journal had an article about how some companies are trying to reduce the stigma around the use of flexible work schedules by their female employees through campaigns aggressively pitching flextime to men. It’s somewhat counterintuitive, but it seems to be working.

Some employers are trying to overcome a perceived stigma on flexible work schedules — often viewed as a concession to women — by redefining the issue as a quality-of-life concern for everyone. The approach is gaining traction, especially in the male-dominated financial-services sector, where employers have long struggled to retain and promote women.

Among the techniques companies are testing: highlighting successful men who have tapped flexible work arrangements; encouraging more employees to work from home part of the time; and promoting alternative career paths.

Ernst & Young displayed a 9-foot poster in Times Square as part of a campaign to spotlight successful men who value their personal lives. Lehman Brothers is presenting their initiative encouraging employees to occasionally work from home as contingency planning for a disaster. But ultimately the goal is to destigmatize flex schedules to retain women and recruit younger workers by making the issue gender neutral.

The article includes several tips from human resource experts for removing the stigma, which could also be applied to social marketing programs for issues like AIDS, disability and mental illness (bold is theirs, nonbolded is mine):

- Use men in promotional materials for flexible-work options – Social marketers should consider using people who are NOT the primary target audience in their imagery to make it seem acceptable to everyone. For example, in a campaign aimed at encouraging people with disabilities to become a volunteer, use pictures of people with different ability levels volunteering so it is shown as something that every person could and should do.

- Make a business case for telecommuting, such as planning for a disaster – Identify other acceptable reasons for participating in the program or taking an action besides the one associated with the stigma. So in promoting the new HPV vaccine, emphasize the fact that it will protect a teenager from cervical cancer rather than from an STD. Or a college-based mental health screening day (obviously not billed as such) might be trying most to reach students at risk of depression but also reach out to people who are stressed out, not sleeping well, or having problems concentrating on their studies.

- Customize career paths for all workers, and encourage alternative paths – Show people in different audience segments, including the one you are most trying to reach, how they can benefit from the program or action. Let them figure out themselves what most applies to their situation. Rather than having nature trails specifically labelled as being for people with disabilities (and which trails are appropriate for which kind of disability), highlight the level of accessibility of each trail for everyone to apply to their own situation, including people with strollers or the elderly – e.g., whether it is paved, has uneven surfaces, guide ropes, stairs, ramps, etc.

- Offer concierge services that simplify life, such as emergency day care – As always, make it easy for people to take the action you are promoting. If they have to go out of their way to do it, it probably won’t happen. An article (subscriber access only) on the front page of today’s Wall Street Journal discusses a proposal to screen all pregnant women for the genital herpes virus. Instead of having a pregnant woman bring herself in to get checked, or letting the doctor decide whether someone is at risk or not, it would just be part of the routine prenatal testing she is doing anyways, and the fact that everyone has to have it reduces any stigma to getting tested for herpes.

Though it seems strange to think about directing your marketing efforts to other audiences besides the one you most want to reach, sometimes you have to take a detour in order to get to your destination.

Photo credit: Soferet

Technorati Tags: stigma, work, marketing, hiv, aids, disabilities, mental illness

by Nedra Weinreich | Oct 13, 2006 | Behavior Change, Blog, Social Marketing

David Roberts on the Gristmill blog shares what he learned from Malcolm Gladwell (author of The Tipping Point and Blink

and Blink ) when he gave a keynote address about social change at a luncheon in Seattle:

) when he gave a keynote address about social change at a luncheon in Seattle:

Stripped of the anecdotes, the basic thesis of the talk was that social change has three somewhat unexpected features:

- It almost always happens faster and cheaper than anybody predicts. See: Berlin Wall falling.

- It is typically brought about not by people with great political or economic power, but by people with great social power — “connectors,” as he calls them. These are folks who are part of an unusually large number of social circles, who can bring disparate groups together.

- It usually happens after a seemingly intractable problem has been reframed. The example here was the spread of seatbelt use in the U.S. For a long time it was a “government meddling” issue. Then a bunch of child-restraint laws were passed, and little Johnny started asking mom why she didn’t buckle up, and it became a “family responsibility” issue. In a matter of just two or three years, seatbelt use rates soared from 15% to 65%.

So, although social change can be somewhat unpredictable (see #1), we can set the stage for it and work to create the conditions in which it can happen (see #2 and 3).

Think about who your “connectors” are for your audiences and how you can hook into their networks. And see if you might be able to reframe the issue so that it connects with the core values of the people you are trying to reach. For example, the issue of school choice has been defined by its opponents (primarily teachers’ unions) as an attack on public schools and teachers that subsidizes private and religious schools. But if you reframe the issue as one of social justice — that poor children are being denied their right to a good education — or one of government waste — that taxpayer funds are being inefficiently used by the bloated and overbureaucratized school system — then you might be able to mobilize new constituencies that had not previously thought about the issue in that way.

One of the commenters to the post, CyberBrook, shared some useful information on community organizing for social change. I especially liked the “M Factor” organizing template:

mission (plan)

message (what’s the point?)

mainstreaming (creating cultural resonance)

money (funding and resources)

mechanics (how to)

mapping (where best to organize, where best to marginalize)

might (strength and power)

marketing (getting the message out in appropriate ways)

media (using the mass media, supporting / creating alternative media)

management (organization)

measurement / market research (feedback)

mobilization (getting people organized and involved, developing capacity and leadership)

It’s like our social marketing Ps but from a community organization angle. The rest of the comments are also worth checking out.

Technorati Tags: social change, marketing, gladwell

by Nedra Weinreich | Oct 10, 2006 | Behavior Change, Blog, Social Marketing

In recent years, college campuses (and other community settings) have increasingly been adopting the social norms marketing approach to reducing things like binge drinking, drug use and smoking by their students. The idea behind this approach is that people will avoid unhealthy activities if they think that most other people around them are doing it too. So, if college students think it’s normal for people to each drink a six-pack of beer at a party, they will be more likely to engage in unhealthy levels of drinking. By publicizing the statistics of how few students at that campus actually do drink that much alcohol in one sitting, showing that the norm is to drink moderately, the model suggests that students will be less likely to binge drink themselves.

In recent years, college campuses (and other community settings) have increasingly been adopting the social norms marketing approach to reducing things like binge drinking, drug use and smoking by their students. The idea behind this approach is that people will avoid unhealthy activities if they think that most other people around them are doing it too. So, if college students think it’s normal for people to each drink a six-pack of beer at a party, they will be more likely to engage in unhealthy levels of drinking. By publicizing the statistics of how few students at that campus actually do drink that much alcohol in one sitting, showing that the norm is to drink moderately, the model suggests that students will be less likely to binge drink themselves.

This approach has quite a bit of documented success. According to the National Social Norms Resource Center, some examples of the effectiveness of this type of project in addressing high-risk drinking include:

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges — 32% Reduction over 4 years

- Northern Illinois University — 44% Reduction over 9 years

- Rowan University — 25% Reduction over 3 years

- University of Arizona — 27% Reduction over 3 years

- University of Missouri at Columbia — 21% Reduction over 2 years

- Western Washington University — 20% Reduction in the first year

But what if there is actually a substantial proportion of the population that does engage in the undesirable behavior? You could still say that “a majority of West Knippenquad University students do not smoke pot,” if 51% say they abstain. But is that a meaningful statement? Even if only 20% of the population uses drugs, that is still one out of five people — not an insignificant figure. Among certain subgroups, the percentage might be much higher.

A recent study published in the Journal of Health Communication backs up these concerns. Not surprisingly, the study found that friends have a greater influence on students’ drinking behavior or beliefs about drinking on campus than social norms campaigns. The social norms messages are not believable if they do not square with what students have observed in their own experience among their friends and acquaintances.

A survey of 277 college students at a northeastern university found that nearly 73 percent did not believe the norms message that most students drink “0-4” drinks when they party. Of that group, nearly 53 percent reported they typically drank five or more drinks at one sitting. To illustrate the influence of social networks, 96 percent of the 5-plus-drink group said their friends drank a similar amount and believed that “other students” on campus drank a similar amount.

“Disbelief in the campaign message may have resulted from the behavior observed by students among their friends and acquaintances, which contrasted with the 0-4 message,” said co-author Ann Major, professor of communications and director of the Jimirro Center for the Study of Media Influence at Penn State. “Also, some students may discount social norms campaigns as an attempt by university administrators to control their behavior.”

Perhaps the social norms approach works among those students who are on the fence about engaging in an unhealthy behavior, and just need a little reinforcement to help them do what they would be inclined to do otherwise. Other types of approaches — social marketing, policy enforcement, or counseling — might be necessary to reach the more diehard partiers who already have set expectations for what is appropriate.

I am also made more skeptical about this approach with the announcement of the establishment of the National Social Norms Institute at the University of Virginia with a $2.5 million grant from the Anheuser-Busch Corporation. I’m glad that many campuses have had success with social norms marketing, but I do hope that it will not be seen as the magic bullet across all subgroups — especially for those most in need of some type of intervention.

Technorati Tags: social norms, marketing, social marketing, alcohol, college

As I was catching up with my pile of unread Wall Street Journals, I came across a couple of articles that at first glance had nothing in common.

As I was catching up with my pile of unread Wall Street Journals, I came across a couple of articles that at first glance had nothing in common.

Nedra helps nonprofits and public agencies create positive change on health and social issues through social marketing and transmedia storytelling strategies at Weinreich Communications since founding the company in 1995. She helps organizations make a difference for the populations they serve by strategically designing programs that draw on state-of-the-art behavior change techniques, digital media approaches and the power of stories.

Nedra helps nonprofits and public agencies create positive change on health and social issues through social marketing and transmedia storytelling strategies at Weinreich Communications since founding the company in 1995. She helps organizations make a difference for the populations they serve by strategically designing programs that draw on state-of-the-art behavior change techniques, digital media approaches and the power of stories.